This is an updated version of the original post from February 22, 2017.

This tutorial introduces contour plots, and how to plot them in ggplot2.

What is a contour plot?

Suppose you have a map of a mountainous region. How might you indicate elevation on that map, so that you get to see the shape of the landscape?

The idea is to use contour lines, which are curves that indicate a constant height.

Imagine cutting the tops of the mountains off by removing all land above, say, 900 meters altitude. Then trace (on your map) the shapes formed by the new (flat) mountain tops. These curves are contour lines. Choose a differential such as 50 meters, and draw these curves for altitudes …800m, 850m, 900m, 950m, 1000m, … – the result is a contour plot (or topographic map, if it’s a map).

In general, contour plots are useful for functions of two variables (like a bivariate gaussian density).

We’ll look at examples in the next section.

Notes on contours:

- They never cross.

- The steepest slope at a point is parallel to the contour line.

- They aren’t entirely ambiguous. For example, you can’t tell whether or not the mountains are actually mountains, or whether they’re holes/valleys! Sometimes you can add colour to indicate depth; other times (like in topographic maps) you can indicate elevation directly as numbers beside contour lines. Other times, this is not required, because the context makes it obvious.

There are two ways you can make contour plots in ggplot2 – but they’re both for quite different purposes. Let’s load ggplot2 through the tidyverse:

library(tidyverse)

theme_set(theme_minimal())Method 1: Approximate a bivariate density: geom_density2d()

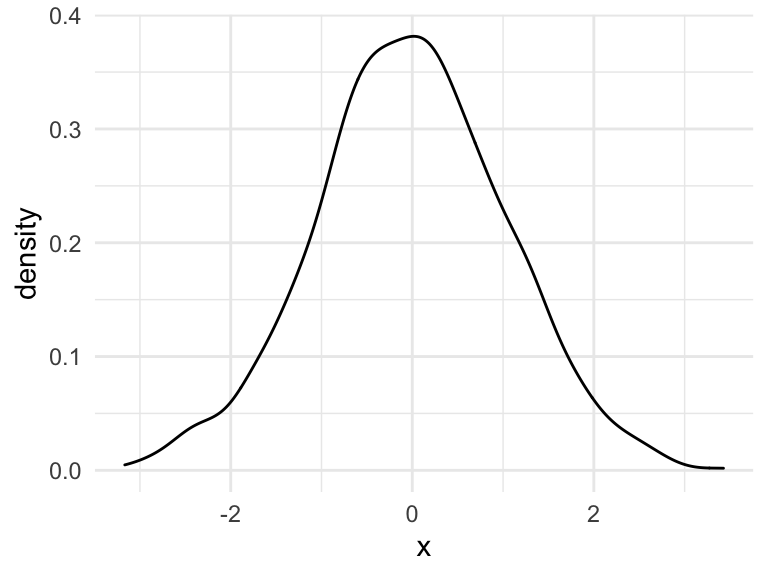

This method approximates a bivariate density from data.

First, recall how this is done in the univariate case. A little kernel function (like a shrunken bell curve) is placed over each data point, and these are added together to get a density estimate:

set.seed(373)

x <- rnorm(1000)

tibble(x = x) %>%

ggplot(aes(x)) +

geom_density()

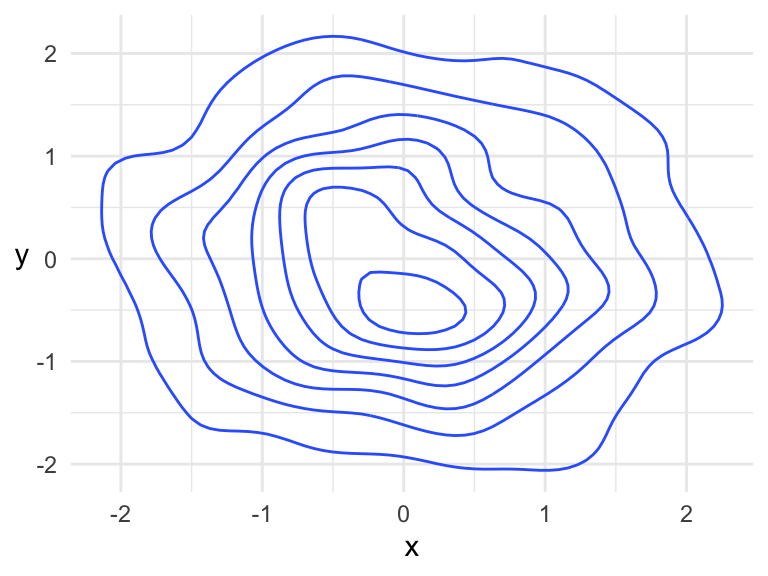

We can do the same thing to get a bivariate density, except with little bivariate kernel functions (like shrunken bivariate Gaussian densities). But, we can’t just simply put “density height” on the vertical axis – we need that for the second dimension. Instead, we can use contour plots.

This is the contour plot that ggplot2’s geom_density2d() does: builds a bivariate kernel density estimate (based on data), then makes a contour plot out of it:

y <- rnorm(1000)

tibble(x = x, y = y) %>%

ggplot(aes(x, y)) +

geom_density2d() +

theme(axis.title.y = element_text(angle = 0, vjust = 0.5))

Based on context (this is a density), we know that this is a “hill” and not a “hole”. If you were to start at some point at the “bottom” of the hill, the steepest way up would be perpendicular to the contours. The highest point on the hill is within the middle-most circle.

Method 2: General Contour Plots: geom_contour()

You can also make contour plots that aren’t a kernel density estimate (necessarily), using geom_contour(). This is based off of any bivariate function.

Basics

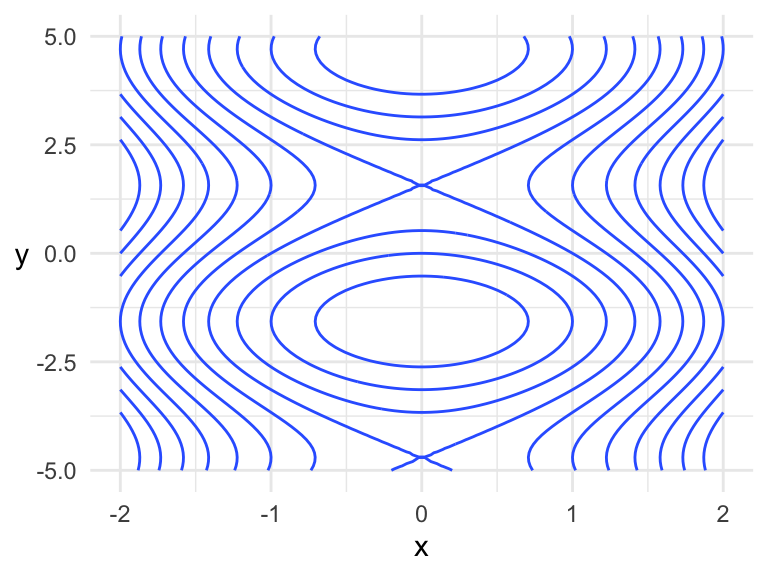

Suppose we want to make a contour plot of the bivariate function \[f(x, y) = x ^ 2 + \sin(y)\] over the rectangle \(-2<x<2\) and \(-5<y<5\).

- Make a grid over the rectangle. It must be a grid –

geom_contour()won’t work otherwise. Theexpand_grid()function is handy for this, filling in all combinations of its input.

f <- function(x, y) x ^ 2 + sin(y)

x <- seq(-2, 2, length.out = 100)

y <- seq(-5, 5, length.out = 100)

(dat <- expand_grid(x = x, y = y))## # A tibble: 10,000 x 2

## x y

## <dbl> <dbl>

## 1 -2 -5

## 2 -2 -4.90

## 3 -2 -4.80

## 4 -2 -4.70

## 5 -2 -4.60

## 6 -2 -4.49

## 7 -2 -4.39

## 8 -2 -4.29

## 9 -2 -4.19

## 10 -2 -4.09

## # … with 9,990 more rows- Evaluate the function at each of the grid points. Make sure you end up with a data frame with three columns: two for the

xandycoordinates, and one for the evaluated function (calledzbelow).

(dat <- mutate(dat, z = f(x, y)))## # A tibble: 10,000 x 3

## x y z

## <dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

## 1 -2 -5 4.96

## 2 -2 -4.90 4.98

## 3 -2 -4.80 5.00

## 4 -2 -4.70 5.00

## 5 -2 -4.60 4.99

## 6 -2 -4.49 4.98

## 7 -2 -4.39 4.95

## 8 -2 -4.29 4.91

## 9 -2 -4.19 4.87

## 10 -2 -4.09 4.81

## # … with 9,990 more rows- Use this data frame with ggplot2’s

geom_contour(). Thexandyaesthetics should be the two grid columns, and thezaesthetic should be mapped to the column with the evaluated function (zhere).

ggplot(dat, aes(x, y)) +

geom_contour(aes(z = z)) +

theme(axis.title.y = element_text(angle = 0, vjust = 0.5))

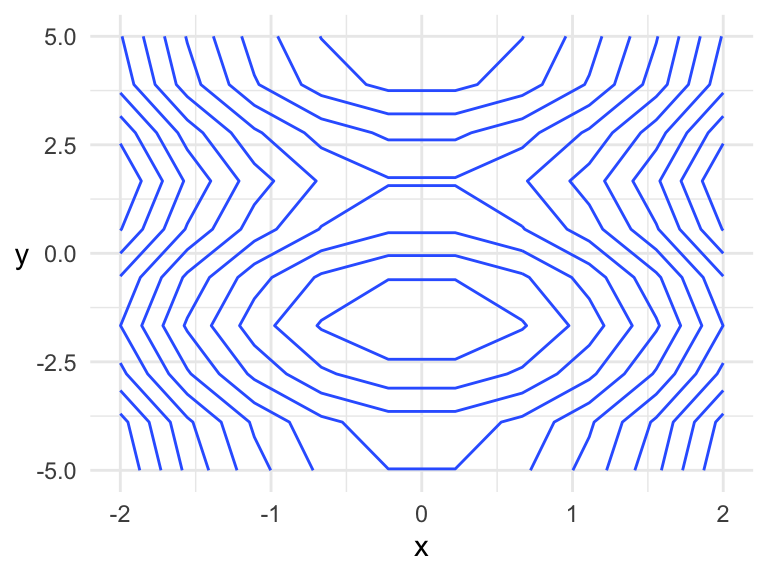

Note that finer grids yield plots with higher accuracy. Here’s an example of a rough grid, whose contours are jagged:

x <- seq(-2, 2, length.out = 10)

y <- seq(-5, 5, length.out = 10)

expand_grid(x = x, y = y) %>%

mutate(z = f(x, y)) %>%

ggplot(aes(x, y)) +

geom_contour(aes(z = z)) +

theme(axis.title.y = element_text(angle = 0, vjust = 0.5))

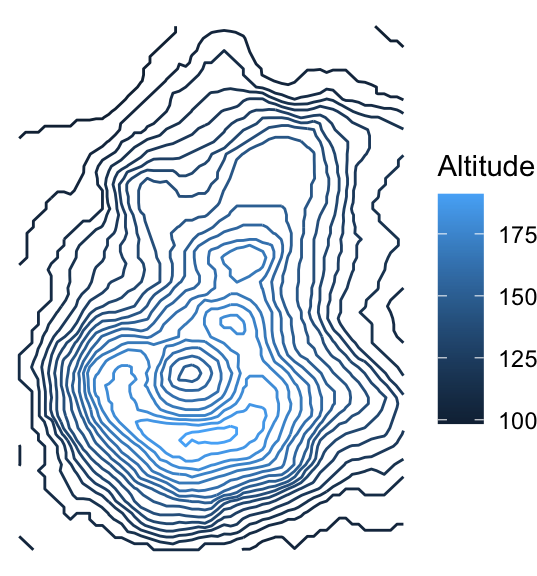

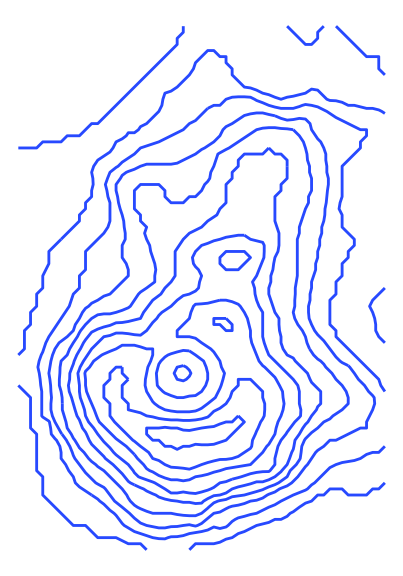

Example using the volcano data

R comes with a dataset containing the altitudes of a volcano, Maunga Whau (Mt Eden), stored in the datasets variable volcano. You’ll notice that the dataset is literally a grid of \(87 \times 61\) altitudes – here are the first six rows and columns:

volcano[1:6, 1:6]## [,1] [,2] [,3] [,4] [,5] [,6]

## [1,] 100 100 101 101 101 101

## [2,] 101 101 102 102 102 102

## [3,] 102 102 103 103 103 103

## [4,] 103 103 104 104 104 104

## [5,] 104 104 105 105 105 105

## [6,] 105 105 105 106 106 106If you’d like, you can take a look at a 3D rendering of the volcano using the rgl package’s surface3d() function. The code for doing this is directly in the documentation of the surface3d() function.

In order to make a contour plot with ggplot2’s geom_contour(), we’ll first need to turn this into a tidy data frame with three columns. You could use as.vector(volcano) to get a vector of altitudes, and line that up with a grid laid out as two columns, but I’m not going to take any chances here, so I’ll opt to use pivot_longer(). We don’t know much about the latitude and longitude, so their values are arbitrary.

(volcano_tidy <- as_tibble(volcano, .name_repair = "universal") %>%

mutate(latitude = 1:n()) %>%

pivot_longer(!latitude, names_to = "longitude", values_to = "altitude"))## # A tibble: 5,307 x 3

## latitude longitude altitude

## <int> <chr> <dbl>

## 1 1 ...1 100

## 2 1 ...2 100

## 3 1 ...3 101

## 4 1 ...4 101

## 5 1 ...5 101

## 6 1 ...6 101

## 7 1 ...7 101

## 8 1 ...8 100

## 9 1 ...9 100

## 10 1 ...10 100

## # … with 5,297 more rowsFix up the longitude (taking the negative to reverse the order, because data are provided as east to west):

(volcano_tidy <- volcano_tidy %>%

mutate(longitude = longitude %>%

str_remove("[\\.]{3}") %>%

as.numeric() %>%

`-`()))## # A tibble: 5,307 x 3

## latitude longitude altitude

## <int> <dbl> <dbl>

## 1 1 -1 100

## 2 1 -2 100

## 3 1 -3 101

## 4 1 -4 101

## 5 1 -5 101

## 6 1 -6 101

## 7 1 -7 101

## 8 1 -8 100

## 9 1 -9 100

## 10 1 -10 100

## # … with 5,297 more rowsNow the contour plot comes for free:

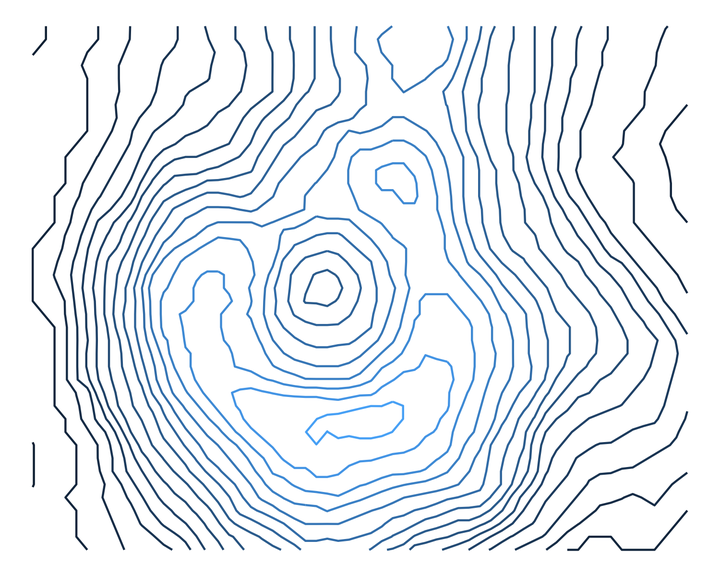

ggplot(volcano_tidy, aes(longitude, latitude)) +

geom_contour(aes(z = altitude)) +

theme_void()

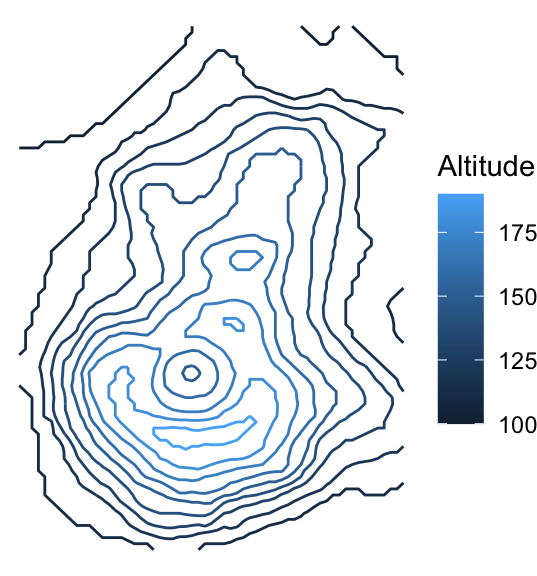

But, you can’t tell that the inner circles actually represent a hole (a caldera), not a peak. Let’s add colour by mapping the ..height.. “variable” to the colour aesthetic of geom_contour(). This will also create a legend for altitude.

ggplot(volcano_tidy, aes(longitude, latitude)) +

geom_contour(aes(z = altitude, colour = ..level..)) +

theme_void() +

scale_color_continuous("Altitude")

We can somewhat tell that the highest point is within the lightest blue area, just below the caldera. But, we would get a better sense of the terrain by adding more contour lines. You can use the bins argument in the geom_contour() function to indicate the number of altitudes for which to draw contours, or binwidth to specify a range of altitudes. Let’s make 20 contours with bins = 20:

ggplot(volcano_tidy, aes(longitude, latitude)) +

geom_contour(aes(z = altitude, colour = ..level..), bins = 20) +

theme_void() +

scale_color_continuous("Altitude")